UNCOVERED HOLLYWOOD SERIES

PRIDE 50th CELEBRATION

Half A Century of Protest - Pride to BLM Along Hollywood Boulevard

Contributed by Lindsay Mulcahy

On Sunday, June 7th, thousands upon thousands of feet pounded down the Walk of Fame and into the Boulevard. Music emanated from car speakers and drum kits, drawing a crowd of 10,000 people at the corner of Hollywood and Vine. Coalescing at the intersection from all corners, protestors flowed West down the Boulevard in a loose synchronism. While protestors’ faces were concealed by masks, their voices were clear. “Black Lives Matter,” they chanted. Calls to “Say their names – George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade,” rang out through the streets. Notably, there was no sign of LAPD. Instead, people passed out snacks, water, and masks, while others wove in and out of the crowd with voter registration forms and trash bags. Several signs declared the presence of street medics, a potent reminder of the violence LAPD officers have inflicted on civilians over the preceding weeks. The march, led by Black Lives Matter Los Angeles, BLD PWR, and rapper YG, was named the biggest congregation since the national uprisings spurred by the murder of George Floyd by the Minneapolis Police Department.

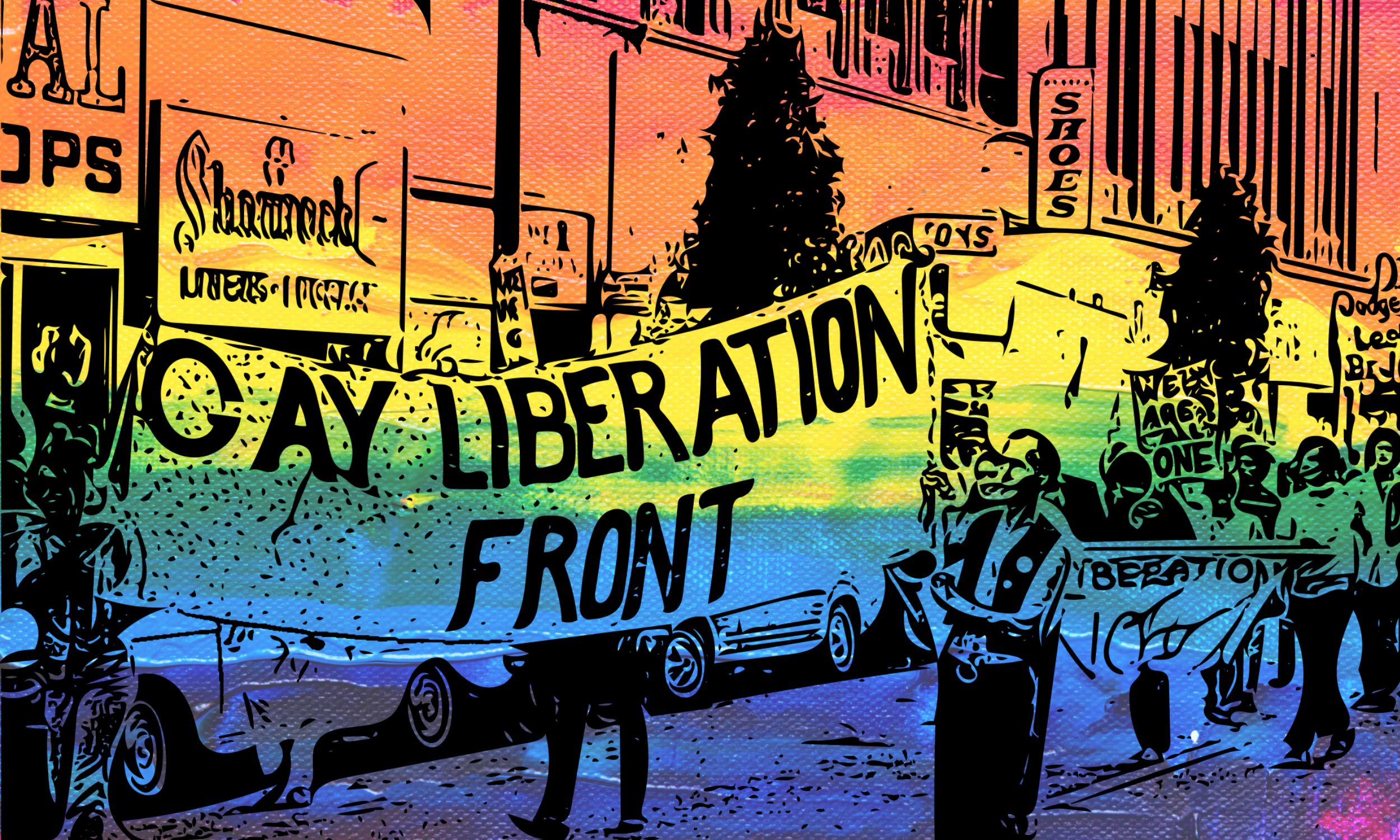

50 years ago, the Boulevard was the site of another historic march against police brutality. On June 28th, 1970, over one thousand people congregated at the corner of Hollywood and McCadden to commemorate the Stonewall rebellion in New York the year before. Organized by the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), protestors took to the streets despite LAPD’s refusal to issue a permit for the parade. (1) Hollywood Boulevard served as the backdrop for the Christopher Street West Pride Parade until 1979 when it moved to West Hollywood.

Plaque commemorating the first Pride March - McCadden at Hollywood Boulevard.

The historic 1970 L.A. Pride Parade has inspired half a century of parades across the world. However, the first pride, as the mantra goes, “was a riot.” On June 28th, 1969, a police raid on the Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street incited six days of protests as queens and activists including Marsha P. Johnson and Silvia Rivera took to the streets. In the years leading up to the Stonewall Rebellion, resistance to police surveillance and violence led largely by queer and trans people of color was gaining momentum across the country. In Los Angeles, protests at Cooper’s Donuts in DTLA in 1959, The Black Cat in Silverlake in 1967, and The Patch in Wilmington in 1968 reveal a growing movement. (2) The turn of the decade signaled a shift from the assimilationist efforts of the homophile movement to gay liberation. Influenced by the Civil Rights Movement, organizers sought to cultivate a queer political consciousness, provide social services, and take direct action. (3)

The choice of the Boulevard for the 1970 march was a strategic one. By the 1920s, the film industry had put Hollywood on the global map. Over the next few decades, the neighborhood cultivated the rise of radio, television, record industries and became a hub of nightlife and entertainment for culture makers. While by the 1950s tourism was the main industry, the image of the Boulevard became solidified in national memory. “It’s a world-famous street,” said founding member of the Los Angeles GLF chapter Morris Kight in 1970. “We wanted to be where the people were, where the media were, where the action was." (4)

Hollywood’s claim as a hub for gender nonconformity and sexual freedom dates back to at least the 1930s where at least six nightclubs located on the Boulevard or nearby were known to serve queer clientele and “female impersonators.” (5) LA’s first openly gay bar actually opened on New Years Eve in 1929. Jimmy’s Backyard, located on 1608 Cosmo, was one of several spots to take advantage of the Pansy Craze of the early 1930s.

Hollywood stars like Greta Garbo, Marliene Dietrich, and Katherine Hepburn bucked gender stereotypes in the public realm and engaged in same-sex relationships in private. The home of Ben Carter, an African American casting agent, was the site of parties that defined Black gay life in early Hollywood. (6) During World War II, the arrival of naval and defense workers led to a surge in bars catering to gays and lesbians, including House of Ivy on Las Palmas and the Windup on Melrose. (7) In an era marked by physical violence and austricization, these semi-private spaces were hallowed ground for LBGTQ+ people to revel, express themselves, and build community.

The historic segregation of LGBTQ+ communities complicates the notion of safe spaces. With some exceptions, racism at the institutional and personal level divided the city. As early as the City of Hollywood’s incorporation into LA in 1910, white residents organized to keep African Americans, Asian Americans, and other communities of color out. (8) In 1939, the federal agency Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) redlined Los Angeles. The hills and western portion of Hollywood were coded blue and green, meaning predominately white, while the southern and eastern portion were yellow and red where HOLC warned of a “threat of infiltration of subversive racial elements.” (9) Homophile organizations of the 1950s and 1960s, too, were largely restricted to white, middle to upper class gays and lesbians.

By the 1970s, organizations such as Los Angeles GLF saw the struggle for sexual and gendered freedom as interconnected with racism and imperialism. However, non-white cis-male members including African American committee chair Greg Byrd, transwoman Angela Douglas, and white lesbians Del Whan and Brenda Weathers were in the minority. (10) Semi-public spaces created for and by queer and trans people of color, ranging from the historic Black disco Catch One to political organizations such as Connexxus, emerged across the city in the 1970s and 1980s.

Morris Kight Square Commemorative sign.

1608 Cosmo - home of Jimmy’s Backyard. The first openly gay bar in Los Angeles.

Circus Disco - Clown Entrance at Night.

An image of a Christmas celebration at Circus Disco.

Issues of solidarity, intersectionality, and safety play out across the landscape. Plans for this year's Christopher Street West L.A. Pride Black Lives Matter march, which highlighted 50 years of “strong and unified partnership” with LAPD but failed to consult with BLMLA, was canceled due to backlash. The resulting All Black Lives Matter march, organized by an entirely Black LGBTQ+ coalition, was for some a place to recognize their intersectional identities, being Black as well as being queer in all its complexities. For others, the event was a reminder of the work to come to center the leadership of the most marginalized people within the queer community. According to journalist and producer Imara Jones,

"The only way forward is to return the movement to its roots. By placing trans women of color at the center of the LGBTQ movement, we will center their issues. And by building this intersectional fight, we will actually advance the interests of the majority." (15)

Councilmember O’Farrell’s decision to protect the All Black Lives Matter street instillation and commemorate the march asks us to consider the role of preservation in social movements. How does one tangibly commemorate the ephemeral movement of bodies through space? What about the landscape- from the low, unassuming brick buildings that sheltered underground queer communities, to the iconic towering Capitol Records and Saving and Loans building- makes Hollywood Boulevard the site of protest after protest? Lastly, how can we capture the complexities of these moments, both the triumphs and failures, to tell an inclusive history and inspire future movements for social change?

Footnotes:

1. Moira Kenney, Mapping Gay L.A. : The Intersection of Place and Politics (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001), 167

2. SurveyLA Los Angeles Citywide Historic Context Statement, “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender (LGBT) Context Statement” prepared for the Office of Historic Resources (Department of City Planning, City of Los Angeles, September 2014), accessed June 20, 2020, https://planning.lacity.org/odocument/23b499c0-1f2e-49cc-842e-8744c439acf6/LosAngeles_LGBT_HistoricContext.pdf, 25, 29.

3. Susan Stryker, Transgender History (Berkeley, CA: Seal Press, 2008), 63.

4. Quoted Kenney, Mapping Gay L.A 167

5. SurveyLA Los Angeles Citywide Historic Context Statement, “LGBT Context Statement,” 43-46.

6. Lillian Faderman and Stuart Timmons, Gay L.A. : A History of Sexual Outlaws, Power Politics, and Lipstick Lesbians (New York: Basic Books, 2006), 45.

7. Circus Disco, Historic Cultural Monument Application

8. SurveyLA Los Angeles Citywide Historic Context Statement, “Context: Japanese Americans in Los Angeles, 1869-1970,” prepared for the Office of Historic Resources (Department of City Planning, City of Los Angeles, August 2018), accessed May 20, 2020, https://planning.lacity.org/odocument/bf97b9b9-cb81-4661-8d20-62c02b9c1415/SurveyLA_JapaneseAmericanContextandResources_Aug2018.pdf, 13.

9. "Security Map of Los Angeles County Area No. C-83," Home Owners' Loan Corporation, February 2, 1939, accessed via Josh Begley, "Redlining California, 1936-1939," accessed June 15, 2020, https://joshbegley.com/redlining/losangeles.

10. Faderman and Timmons, Gay L.A, 176.

11. James Rojas, "From The Eastside to Hollywood," KCET, September 2, 2016, accessed June 20, 2020, https://www.kcet.org/shows/lost-la/from-the-eastside-to-hollywood-chicano-queer-trailblazers-in-1970s-la.

12. Phillip Zonkel, "Can Circus Disco be saved from demolition?," April 1, 2015, quoted from Hollywood Heritage, "Circus Disco Historic Cultural Monument Nomination Form," November 17, 2015.

13. Circus HCM,David Johnston and Henry Mendoza, "Police Attitude on Gay Bars Assailed by 4 on Council," Los Angeles Times May 1, 1980, quoted from Hollywood Heritage, "Circus Disco Historic Cultural Monument Nomination Form."

14. Kenney, Mapping Gay LA, 18.

15. Imara Jones, "Trans Women of Color are the Past and Future of LGBTQ Liberation," The Nation, June 27, 2019, accessed June 27, 2020, https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/trans-women-color-lgbtq-stonewall/.

In 1968, a book entitled "Hollywood: Gay Capitol of the World," aggrandized the area as a nerve center of gay life. The 1960s and 1970s saw the flourishing white gay male community, who socialized and danced along the Boulevard at Arthur J’s and the Golden Cup. Queer people of color also carved out space in Hollywood. Artist and activist James Rojas described intimate, nondescript venues like Other Side and Circus Disco where he and his friends “communicated with our bodies – an essential, enduring part of our queer development and identity.” The lack of gay visibility in East LA encouraged Rojas and his friends to build community "out of the margins by fusing our Latino cultural values within the predominant gay white male landscape.” (11)

In 1975, Gene La Pietra and Ermilio (“Ed”) Lemos opened Circus Disco on the corner of Santa Monica and Lexington after their non-white friends were barred from Studio One in West Hollywood. Circus Disco, said documentarian Jonathan Mendez, was a “sacred cultural space." (12) More than just a dancehall, La Pietra hosted political fundraisers and events with guest speakers including Cesar Chavez and Jane Fonda, encouraging the politicization of queer people. It was also a site of contention; after repeated LAPD raids in 1980, La Pietra spoke out against police discrimination. City Councilmembers critiqued LAPD for “devoting too much attention to gay bars and not enough to serious crime.” (13) Until 2015, Circus Disco served as a key community space for the Latinx gay community and the LGBTQ+ community at large.

According to historian Moira Kenney, “the city is not a clean slate onto which to build something new, but a thing constructed, onto which activists and communities layer new meaning.” (14) Movements for LGBTQ+, Black, Latinx, and other forms of liberation continue to make history on the Boulevard. The strategic decision by Black Lives Matter Los Angeles (BLMLA) and other organizers to stage actions in Hollywood and other historically white, wealthy communities indicates the multifaceted political dynamics of public space.

FURTHER RESOURCES

Our colleagues at Lavender Effect, a wonderful advocacy group for the LGBTQ community has an excellent interview with Rev. Troy Perry, who was one of the three organizers of the first Pride March.

Check out the Highlights HERE.

Or the full 90 minute interview HERE.

They also have a very entertaining self guided walking tour exploring the LGBTQ history of Hollywood Boulevard. You can check that out HERE.

To learn more about local activities and actions you can take regarding Black Lives Matter, make sure to check out the website for the Los Angeles Chapter HERE.

There is also an amazing 3D Tour of the Stonewall Inn from CyArk, a company that creates interactive and immersive experiences of Heritage Sites. Check it out HERE.