UNCOVERED HOLLYWOOD SERIES

Finding Safe Haven in Hollywood - The Travelers’ Green Book

Contributed by Lindsay Mulcahy

Turning south from Hollywood Boulevard onto Wilcox Avenue, one might be tempted to speed past the Mark Twain Hotel, a modest three-story building awash in soft pink stucco. For Black travelers in the 1950s, however, the building’s neon sign signaled safety along Route 66.

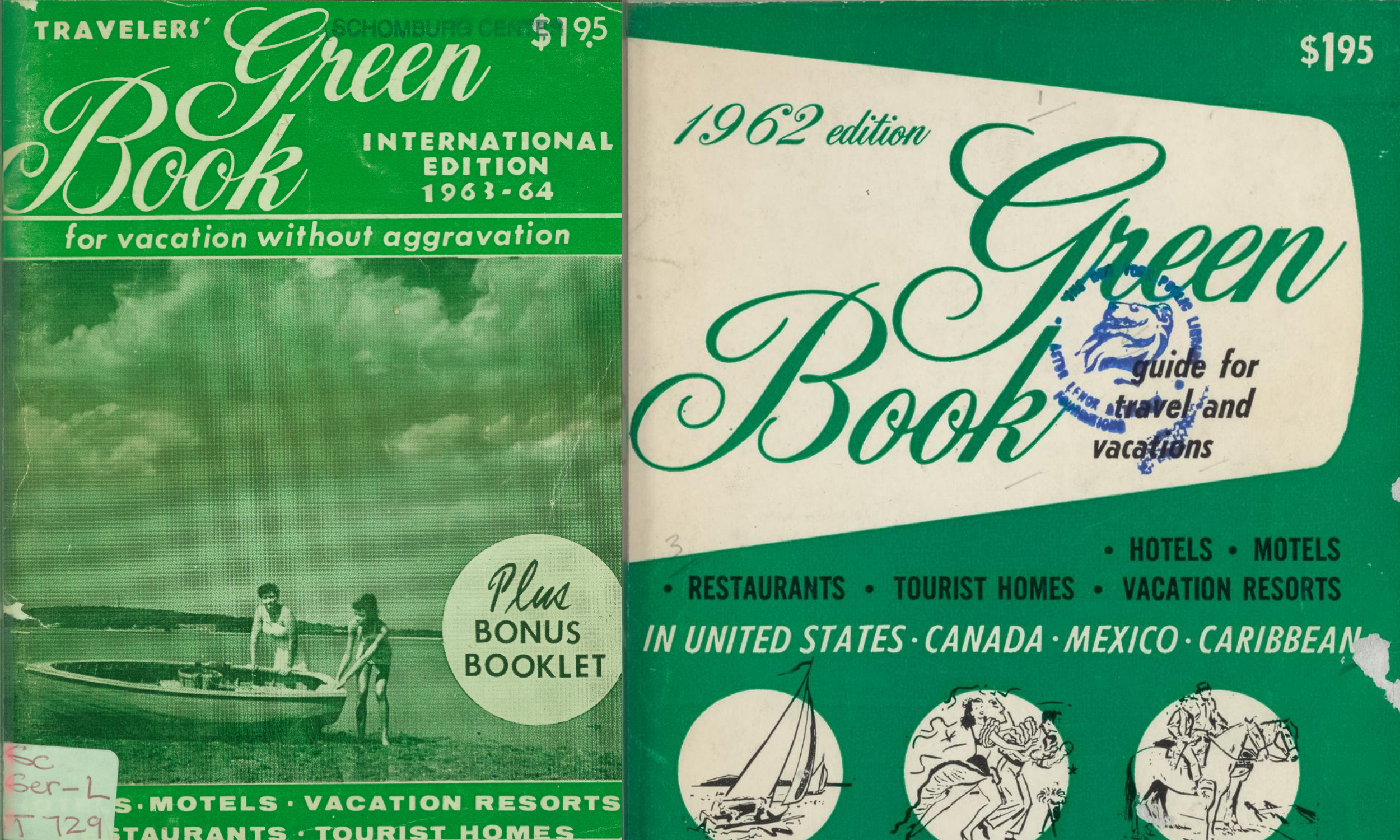

In the early twentieth century, booster materials depicting verdant landscapes, sunny beaches, and motion picture stars fueled Los Angeles' growing population and tourist economy. In the 1920s, the rise of automobiles further transformed the landscape as a growing web of pavement carried travelers across the country. However, the “open road,” explained photographer and historian Candacy Taylor, “was not open to all.” [1] Jim Crow laws, all-white "Sundown Towns," and the looming threat of violence severely limited where Black travelers could eat, drink, and sleep. In 1936, Victor Hugo Green published the first Negro Motorist Green Book in New York. While the Green Book was one of numerous travel guides that helped African Americans navigate space, it proved to be the most enduring and was published annually until 1967.

The Green Book was an early example of crowdsourcing where Black travelers shared their experiences to help future travelers navigate new areas and support businesses owned or operated by Black people. Each issue encouraged readers to send in known locations “so that we might pass along to the rest of your fellow Motorists” and “giv[e] added employment to members of our race.” Between advertisements for hotels and restaurants, the pages also educated travelers about Jim Crow laws and civil rights. [2]

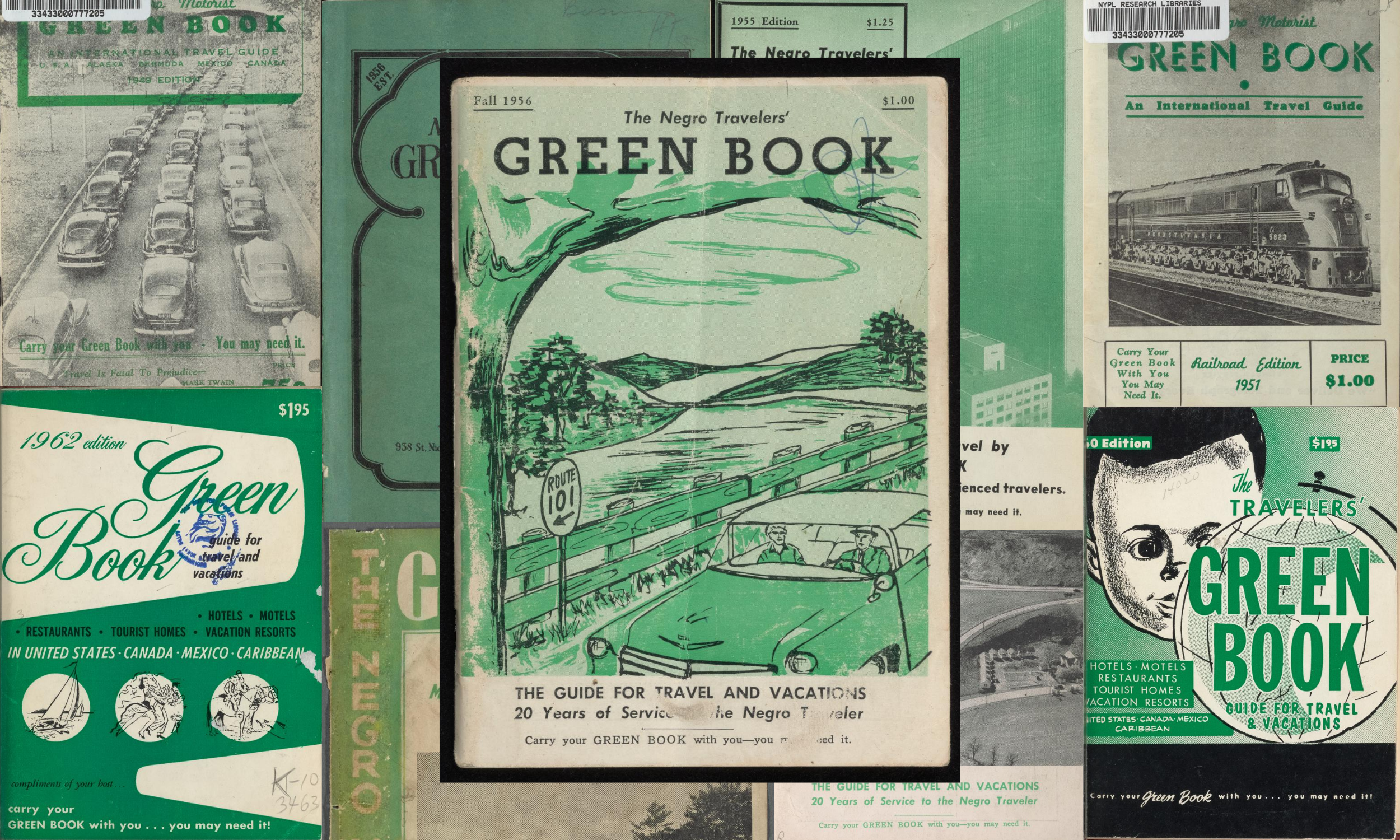

Selected pages from Green Book Editions. Courtesy of New York Public Library.

Collection of editions of the Green Book - Courtesy of the New York Public Library

Los Angeles first appeared in the Green Book in 1939 with several accommodations along Central Avenue, the commercial and cultural corridor hailed as “the Black belt of the city” since the 1910s.[3] In the early 1900s racial segregation in Los Angeles was sporadic. However, the rising Black population in the 1930s and 1940s was met with a growing backlash from white residents. Many Black Southerners moved West to escape violence and disenfranchisement, but as historian Jack Forbes described, they found Southern California to be a “Jim Crow society difficult to change because its forms of discrimination stemmed largely from attitude rather than law.” [4]

Racial housing covenants restricted Black residences to parts of South LA, while Padasena, Santa Monica, and Manhattan Beach maintained white-only pools and beaches, and "Sundown Towns" like Burbank and Glendale were openly hostile to Black Angelinos. Taylor stated, “in some regards people there [in the South] were sometimes safer because there were clear signs. You knew where you could and couldn’t be.” [5] The Green Book clarified the racially-coded landscape by identifying certain sites in white enclaves, including Hollywood, that were marked as safe for Black travelers.

“There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal rights and privileges in the United States.”

The home of a James W. Brown on Seattle Drive, described as a “quixotic…. sprawling estate located high in the Hollywood Hills,” was the first Hollywood site to be included in the Green Book in 1948.[6] “Tourist Homes” like Brown’s were private residences that welcomed travelers. The following year in 1949, the Mark Twain on Wilcox Ave, the Wilcox Hotel on Selma Ave, and Las Palmas Hotel on Cahuenga were added to the list. [7] The three buildings were part of a cluster of low to mid range priced hotels just off the Hollywood Boulevard. The Mark Twain, a small vernacular Mission Revival building, was an affordable Single Room Occupancy (SRO) from its opening in 1921.

Just half a block away, the five story Mediterranean Revival Wilcox hotel was designed in 1926 by Richard M. Bates and in its earlier days catered to a slightly wealthier clientele.[8] Black travelers may have eaten at the Hollywood Restaurant which flickered in and out of the Green Book in the years 1949 and 1952. The restaurant, formerly part of the Fred Harvey Franchise, was located next to the bus terminal on Cahuenga and offered convenience for travelers who had just landed in Hollywood.[9]

Almost a decade later in 1957, the Knickerbocker Hotel appeared in the Green Book. Initially a glamorous location that drew Hollywood elite, over the decades the building and the fates of its residents declined. By the time it was featured in the Green Book, its reputation was marked by several tragedies and ghost stories. Paul R. Williams notably oversaw the hotel's renovation in 1954. [10]

Sites such as the Knickerbocker and Mark Twain tell the story of Hollywood's development in the 1920s as an international destination for commerce and entertainment. Their inclusion in the Green Book adds another dimension to their history and warrants further exploration. Together these locations help visualize the movement of Black travelers, and perhaps residents, through Hollywood.

From the first edition, Victor Green held optimism that for the day when “this book was no longer needed… when we as a race will have equal rights and privileges in the United States.” [11]In the years leading up to the Civil Rights Act, the Green Book testified to the progress for fair access to public accommodations. In 1962, the Green Book's Hollywood section was expanded to include the Plaza Hotel and Hotel Roosevelt, and by 1963 it listed nine Hollywood hotels ranging in cost and convenience. [12]

Mark Twain Hotel Postcard - 1925

Roosevelt Hotel - 7000 Hollywood Blvd

The Mark Twain Hotel 1945 and 2020

The Hollywood Plaza Hotel - 1637 N. Vine

Hollywood Wilcox Hotel - circa 1937 - (now Mama Shelter Hotel) - 6504 Selma Ave.

The Knickerbocker Hotel - 1714 Ivar Ave.

STAFF NOTE:

What struck us was how many of these places are still Hotels, even if they changed names or were demolished. Although some of the locations, like the Imperial “400” Motel, fell into disrepute for a time, they have prevailed. It is a reminder of the many stories a place can hold, if we are willing to listen.

FURTHER RESOURCES

Learn more about Green Book / history of African American leisure and travel:

"Rising Up: African American Sites of Conscience in Manhattan Beach and Santa Monica, CA" and Living the American Dream: African American Leisure Sites during the Jim Crow Era by Allison Rose Jefferson

Overground Railroad: The Green Book and the Roots of Black Travel in America by Candacy Taylor

Driving While Black: Race, Space & Mobility in America directed by Ric Burns

AND

Check out the amazing digital collection of Green Book editions available through the New York Public Library. They are free to download and have interesting articles, not to mention all of the changing safe haven locations around the country. To see more just go to the main page of the collection HERE.

The Sands-Sunset Hotel (1965). It is now a parking lot. 8775 Sunset Blvd.

Hollywood Thunderbird Inn (1950) 8300 Sunset Blvd. It is now the Standard Hotel - Hollywood.

Footnotes:

[1] Candacy A. Taylor, Overground Railroad : the Green Book and the Roots of Black Travel in America (New York: Abrams Press, 2020), 12.

[2] Victor H. Green, Negro Motorist Green Book (New York, 1940).

[3] California Eagle, 2015, quoted in National Park Services, “Historic Resources Associated with African Americans in Los Angeles,” accessed July 13, 2020, https://www.nps.gov/nr/feature/afam/2010/afam_los_angeles.htm.

[4] Frank Norris, “Racial Dynamism in Los Angeles, 1900-1964: The Role of the Green Book” (Southern California Quarterly, Vol. 99, No. 3): 272.

[5]Quoted in Carolina A. Miranda, “Q&A: ‘A practical solution to a horrific problem’: When even Los Angeles needed havens for black drivers,” Los Angeles Times, October 24, 2016, accessed July 13, 2020, https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/miranda/la-et-cam-candacy-taylor-green-book-20161020-snap-story.html.

[6] Norris, “Racial Dynamism in Los Angeles,” 281.

[7]Victor H. Green, Negro Motorist Green Book (New York, 1949); Frank Norris, "Route 66 Properties Listed in Black Traveler Guidebooks," National Parks Service, August 2014, accessed July 26, 2020, https://ncptt.nps.gov/rt66/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Rt66GreenBookSurvey.pdf

[8] Los Angeles: A Guide to the City and Its Environs, compiled by Workers of the Writers’ Program of the Work Progress Administration in Southern California, sponsored by the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors (Hastings House, New York, 1941).

In 1964, the book’s then-editors Langley Waller and Melvin Tapley hailed the Civil Rights Act as a victory. They recognized that “the militancy of these civil rights groups exhibited in sit-ins, kneel-ins, freedom rides, other demonstrations and court battles has widened the areas of public accommodations accessible to all.” [13]Hollywood continued to be a contested site for equal rights. In 1963, the NAACP initiated a campaign demanding fair representation and hiring practices for Black artists in Hollywood.[14]

Extant Green Book buildings deepen our understanding of the relationship between the physical landscape and often unseen racial geography. Of the 224 Green Book sites in Los Angeles, only 8 percent remain today. [15] Those that remain may be altered or in poor condition due to the systemic disinvestment of South Los Angeles and even parts of Hollywood, thereby leading to lack of recognition of their historical significance.

In 2014, the Mark Twain Hotel underwent extensive renovation but most of its exterior character defining features remain. Its setting may be further compromised by the proposed construction of a 15-story complex next door. EIR documents for that project currently do not contain adequate protections. While local preservation regulations continue to stress material integrity, preservationists should continue to emphasize the social history of the existing Green Book sites in order to continue to convey their physical presence in the history of Los Angeles.

Las Palmas Hotel - 1920’s - 1738 N. Las Palmas Ave. Courtesy Cal State Library.

Las Palmas Hotel - 2020 - Still in business!

Imperial 400 Motel (1970’s). 6826 W. Sunset.

Carlton Lodge (1949). 2011 N. Highland Ave.

Imperial 400 Motel is now a Rodeway Inn.

Carlton Lodge now a Best Western (2020).

Hallmark House Motor Hotel (1950’s) 7023 Sunset Blvd.

Hallmark House is now a Days Inn (2020). The original structure was demolished.

[9] Norris, "Route 66 Properties Listed in Black Traveler Guidebooks," National Parks Service; Lindsay Ross-Williams, "LAistory: Hollywood's Fred Harvey Restaurant & Cocktail Lounge," LAist, January 10, 2020, accessed July 26, 2020, https://laist.com/2010/01/30/laistory_fred_harvey_on_cahuenga.php.

[10] Hadley Meares, “Off the Boulevard of Broken Dreams: The Knickerbocker Hotel’s Haunted History,” June 19, 2015, KCET, accessed July 13, 2020, https://www.kcet.org/history-society/off-the-boulevard-of-broken-dreams-the-knickerbocker-hotels-haunted-history.

[11] Green, Negro Motorist Green Book (New York, 1940).

[12] Norris, “Racial Dynamism in Los Angeles,” 267.

[13] Langley Waller and Melvin Tapley, Negro Motorist Green Book (New York, 1964).

[14] Christopher Sieving, Soul Searching Black-Themed Cinema from the March on Washington to the Rise of Blaxploitation (Middletown, Conn: Wesleyan University Press, 2011), 13.